Dan Harmon once said that when he was writing Community, he didn’t just want funny episodes…

He wanted every story to feel inevitable.

No wasted scenes. No random jokes. Every character arc had to click into place like a puzzle piece.

So he sketched out a circle on a napkin. Eight steps. Simple, repeatable, airtight. That napkin sketch eventually became what we now call the Dan Harmon Story Circle, the structure behind Community, Rick and Morty, and some of the most watchable TV of the past two decades.

You don’t need a Hollywood budget or a writers’ room to use it either. The circle works just as well when you’re hunched over a laptop at your home office or kitchen table.

In this guide, you’ll learn:

- What the Story Circle is

- A detailed breakdown of all eight steps in the Story Circle

- Examples of the Story Circle in use

- How you can use the Story Circle in your writing

If structure has ever felt intimidating, this will change that. The Story Circle is approachable, versatile, and once you see it in action, impossible to ignore.

What is the Dan Harmon Story Circle?

The Story Circle is a storytelling framework created by screenwriter Dan Harmon. It grew out of Joseph Campbell’s famous “Hero’s Journey,” but Harmon wanted something leaner and easier to use.

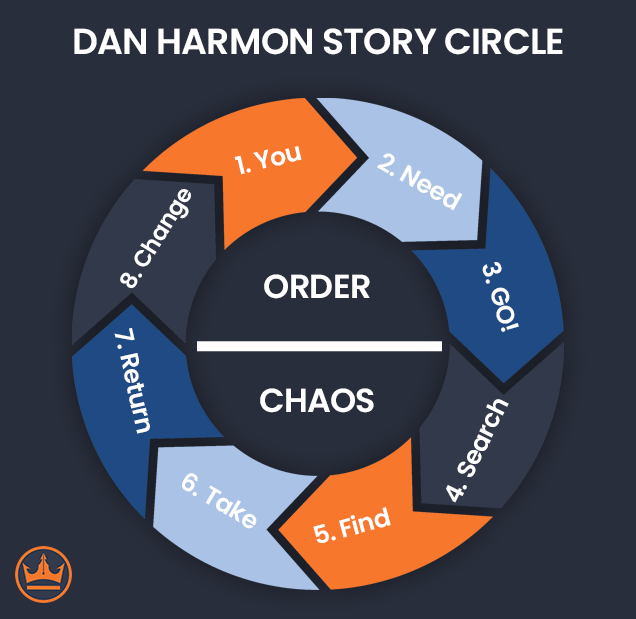

The Hero’s Journey, as outlined by Campbell (and later simplified by Christopher Vogler), has 12 stages. The Story Circle trims that down to 8:

- You – The character is in a zone of comfort.

- Need – Something is missing. They want or need something.

- Go – They enter an unfamiliar situation.

- Search – They adapt to this new world.

- Find – They get what they wanted.

- Take – They pay the price for it.

- Return – They head back to where they started.

- Change – They’re no longer the same person.

Compare that to the Hero’s Journey, which runs through beats like Call to Adventure, Meeting the Mentor, Crossing the Threshold, Ordeal, and Resurrection. Both are about leaving home, facing trials, and returning transformed. Harmon’s version just puts the focus squarely on character growth instead of layering on extra steps.

That focus is what makes the Story Circle so flexible. You’ll see it in myths, novels, and films. You’ll also hear it when a friend tells a story about something that happened to them last weekend.

If the Hero’s Journey feels like a map for epics, the Story Circle feels like a tool you can pull out and start using right away.

Who is Dan Harmon?

Dan Harmon is a television writer and producer best known for creating Community and co-creating Rick and Morty. He’s built a career out of mixing sharp comedy with airtight storytelling.

Earlier in his career, Harmon dove deep into Joseph Campbell’s “Hero’s Journey” and Christopher Vogler’s screenwriting guides. He liked the theory, but not the baggage. Harmon wanted a framework that actually worked in the chaos of a writers’ room… something that could keep a story moving without drowning in mythological jargon.

So he boiled it down into eight steps that we clear, simple, and repeatable. That napkin sketch became the Story Circle, a structure that has since shaped some of the most beloved episodes of television in the past twenty years.

(Here’s a short video of Harmon himself explaining the concept.)

How Does the Dan Harmon Story Circle Work?

Think of the circle as a swing between stability and disruption.

The top half (steps 1–3 and step 8) is about order. The character starts in a familiar place, with routines and comfort. By the time they return at the end, things may look the same on the surface — but the character isn’t the same person anymore.

The bottom half (steps 4–7) is about chaos. This is where the story pushes the character out of their depth. They face trials, temptations, setbacks, and consequences that force them to adapt.

That swing from order to chaos and back again is what makes the Story Circle work. The events matter, but only because of what they do to the character. Each trip around the circle leaves them altered in some way.

| Phase | Step | What It Represents |

|---|---|---|

| Order | 1. You | The character in their comfort zone, living life as usual. |

| 2. Need | Something they want or something missing that creates tension. | |

| 3. Go | They leave the familiar world in pursuit of that need. | |

| Chaos | 4. Search | The character faces trials, new rules, and rising conflict. |

| 5. Find | They get what they wanted, but it comes with strings attached. | |

| 6. Take | The cost of that pursuit hits hard; a price must be paid. | |

| 7. Return | They head back toward the familiar world, changed by the ordeal. | |

| Order | 8. Change | The circle closes. The character is back where they began but transformed. |

The 8 Stages of Dan Harmon's Story Circle

Here’s where the circle comes alive. The eight stages are simple on the surface, but together they map the rise, fall, and transformation of your character.

Each stage has its own role to play and a rough spot in the story’s timeline. Think of them less like rigid checkpoints and more like guideposts or markers that keep your story moving without boxing you in.

Step 1. You (The Character in Their Comfort Zone)

Every story has to start somewhere, and Step 1 is where you show us the character as they are before the storm hits. It’s the “ordinary world” moment — not flashy, not dramatic, just enough to let us see who this person is and what normal looks like for them.

Think of Harry Potter under the stairs, Katniss slipping through the fence to hunt, or even Shrek in his swamp. These aren’t epic scenes. They’re small, grounding moments that give us context. Without them, the rest of the circle doesn’t land because we don’t know what “home base” looked like in the first place.

Tips for writing Step 1 well:

- Give readers a reason to care about your protagonist. That doesn’t mean they need to be likable, but they do need to be interesting or sympathetic in some way.

- Let the character interact with their world. A couple of actions or exchanges will do more than pages of exposition.

- Keep the setup lean. We don’t need a map, a history lesson, or ten side characters in the opening chapter. Just the essentials.

- Keep it brief. Step 1 usually covers about 10–12% of Act I… enough to establish the world and character without overstaying its welcome.

Step 2. Need (Something is Missing)

A story doesn’t move unless the protagonist wants something. It can be obvious and external (Katniss needs to protect Prim, Frodo needs to get the Ring out of the Shire) or quiet and internal (a character longing for connection, respect, or freedom).

Either way, that gap between where they are and what they want creates the spark that pulls them forward.

This need often shows up hand-in-hand with the inciting incident (the event that shakes up the comfort zone and demands change). Sometimes it’s subtle, like a growing dissatisfaction with life. Other times it’s explosive, like a call to adventure they can’t ignore.

The important part is clarity. If readers don’t know what your protagonist wants, they won’t know what to root for.

Tips for writing Step 2 well:

- Make the need specific and relatable. Even big fantasy quests are built on human wants like safety, belonging, or love.

- Tie the need to the character’s internal arc. The external goal might fade, but the deeper need should carry through the story.

- Chronology matters. Step 2 should surface early, usually by the 15% mark of Act I.

Step 3: Go (The Leap Into the Unknown)

This is the turning point where the character steps beyond their comfort zone and crosses into new territory.

Sometimes it’s literal (Katniss leaving District 12, Frodo leaving the Shire). Other times it’s emotional (a character entering a relationship, a job, or a decision that changes everything).

Here, the core conflict of the story comes into focus. The protagonist starts pursuing their goal in earnest, but obstacles appear right away.

It’s the beginning of the real struggle.

Tips for writing Step 3 well:

- Make the central conflict visible. Readers should feel the stakes rise as soon as the character makes this leap.

- Give the protagonist a first taste of real resistance… an obstacle that proves the path forward won’t be easy.

- Even though the character is outside their comfort zone, show that they’re still motivated to act. That tension (fear mixed with drive_ is what pulls readers in.

- Timing tip: Step 3 usually falls around the 25% mark, the start of Act II. By now Act I is finished and the main narrative is underway.

Step 4: Search (Adapting to the Unfamiliar World)

The initial leap is behind them, but now the protagonist faces the reality of the unknown. What looked like a clear path is suddenly messy, complicated, and full of setbacks. They realize they may be in over their head, but turning back isn’t an option.

This stage is all about trial and error. The character experiments, searches for solutions, and learns the rules of this new world. Progress is possible, but it comes at a cost. They fail, try again, and fail better. Along the way, allies may appear, but so do sharper threats.

In The Empire Strikes Back, Luke Skywalker fumbled his training. In Pride and Prejudice, Elizabeth Bennet navigated the social minefield of Mr. Darcy and polite society.

The character doesn't lose sight of their goal, but the obstacles keep multiplying.

Tips for writing Step 4 well:

- Layer in additional conflict. Let the protagonist struggle, regroup, and struggle again.

- If you haven’t already, introduce allies who can help, but make sure they add new complications too.

- Raise the stakes by showing that something (or someone) can be lost in this new world.

- Timing: Step 4 typically lands around the 30% mark of your story. Keep it tight (enough to show adaptation and struggle, but not so long that the story stalls).

Step 5: Find (A False Victory)

At the midpoint, the protagonist gets what they were chasing.

It might be the external goal itself… a prize, a person, a victory. Or it might be an internal breakthrough, a revelation about who they are or what they want. Either way, it looks like success.

But the catch is baked in: what they’ve found isn’t the full answer. Sometimes it’s incomplete, sometimes it’s misleading, and sometimes it simply opens the door to bigger problems.

This is the classic “false victory” — the moment when things appear to be turning around, but in truth the hardest stretch of the journey is still ahead.

Think of Indiana Jones snatching the artifact, only to learn the villains are still on his tail. Or Harry Potter winning a Quidditch match while the deeper danger at Hogwarts continues to build.

The surface win hides the storm brewing underneath.

Tips for writing Step 5 well:

- Show a moment of triumph. Give readers a reason to believe things might be looking up.

- Don’t let the victory last. Use this moment to pivot the story, twist the stakes, and remind readers the conflict isn’t done.

- Match the win to the motivation: an external prize (item, achievement, person) or an internal discovery (self-knowledge, realization).

- Where this fits: Step 5 usually lands right in the middle of your story, at the 50% mark.

Step 6: Take (The Price Must Be Paid)

The false victory doesn’t come free.

In this stage, the protagonist realizes that what they gained in Step 5 carries a heavy cost. It could be a personal sacrifice, a betrayal, or a devastating setback. Either way, it knocks them down hard and forces them to face consequences they can’t avoid.

This is often the lowest point of the story. The character has to confront the gap between what they wanted and what they truly needed. That clash often strips away illusions and leaves them with no choice but to grow.

Simba ran away from Pride Rock after Mufasa’s death. Tony Stark watched his technology fall into the wrong hands. The win that once looked bright now casts a shadow.

Tips for writing Step 6 well:

- Show the weight of the consequences. This is where the character pays dearly for chasing what they wanted.

- Let new challenges spring from the supposed win in Step 5. The “solution” should make things worse, not better.

- Deliver a meaningful loss. It doesn’t always have to be death or destruction, but it should feel like something important is slipping away.

- Pacing note: Step 6 usually falls near the end of Act II, around the 65–75% mark, setting up the climb toward the final act.

Step 7: Return (Back Toward the Familiar World)

After the crash of Step 6, the protagonist makes their way back toward the world they left behind.

Sometimes this return is literal (back to the hometown, back to the people they left). Other times it’s thematic (a return to old relationships, routines, or beliefs). Either way, they aren’t the same person who set out in Step 3.

This return isn’t the happy ending. The world is still tilted, the conflict unresolved.

But now the character has knowledge, skills, or allies they didn’t have before. This step sets the stage for the final confrontation by showing how far they’ve come and what they still have to face.

In The Wizard of Oz, Dorothy makes it back to Kansas, but the lessons of her journey give new meaning to “there’s no place like home.”

Tips for writing Step 7 well:

- Pause here to show the character’s return to something familiar — it highlights contrast with who they were at the start.

- Use this moment to underline change. Even small gestures can show how they’ve grown.

- Remember the story hasn’t settled yet. Chaos still lingers, and the climax is close.

- Structural note: Step 7 marks the start of Act III, usually around the 75% point of the story.

Step 8: Change (The Final Test)

This is the payoff. The protagonist faces the climax of the story… the head-on collision between who they were and who they’ve become.

Everything they’ve gained along the way is put to the test here, and the result shows whether the journey truly mattered.

The conflict can take many forms: a battle, a heartfelt confrontation, a last-chance decision, or an internal reckoning. What matters most is that the character has transformed. They step back into their familiar world, but with the strength or wisdom to shift it in some way.

In The Matrix, Neo returns to the world he once doubted, now fully aware of his power to bend reality itself. The circle closes, but nothing is the same.

Tips for writing Step 8 well:

- Don’t hold back. This should feel like the biggest test in the story — physical, emotional, or both.

- Tie the ending to the beginning. Echoing Step 1 creates resonance and makes the circle feel complete.

- Show not just personal change, but how that change ripples into the world around them.

- Placement note: The climax usually lands between the 85–87% mark. Afterward, leave room for falling action and resolution to tie up loose ends.

Closing the Circle

When you lay the steps out, the Story Circle looks simple.

But that simplicity is what makes it so versatile. Whether you’re writing a novel, a screenplay, or a short story, moving your character through this loop of want, struggle, and transformation gives your story shape.

The circle closes where it began, but the character is never the same.

5 Great Examples of Dan Harmon's Story Circle

Let’s walk through five familiar stories to see the circle in action. None of these were written with Dan Harmon’s steps in mind, but once you know the pattern, you’ll start spotting it everywhere.

Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone

- You: Harry lives under the stairs, unwanted by his aunt and uncle.

- Need: He longs for belonging and learns he’s a wizard.

- Go: Harry boards the train to Hogwarts and enters a world of magic.

- Search: He studies spells, makes friends, and uncovers school secrets.

- Find: He gets what he wants (a sense of belonging) through Quidditch and friendships.

- Take: His hunt for the Sorcerer’s Stone forces him into direct conflict with Voldemort.

- Return: He defeats Voldemort and heads back to the Dursleys.

- Change: He’s no longer the neglected boy under the stairs. He knows he belongs.

The Lion King

- You: Simba is a carefree cub in Pride Rock’s safe world.

- Need: He yearns to prove himself worthy of being king.

- Go: After Mufasa’s death, Simba flees into exile.

- Search: He grows up with Timon and Pumbaa, learning “Hakuna Matata.”

- Find: Simba builds a new life free of responsibility.

- Take: Nala and Rafiki remind him of his duty, forcing him to confront Scar.

- Return: Simba heads back to Pride Rock.

- Change: He claims his role as king, taking responsibility for the Circle of Life.

The Hunger Games

- You: Katniss lives in District 12, struggling to provide for her family.

- Need: She wants to protect her sister and survive.

- Go: Katniss takes Prim’s place in the Games.

- Search: She forms alliances, learns to adapt, and navigates the deadly arena.

- Find: Katniss gains an edge with Peeta’s partnership and public support.

- Take: She risks everything by defying the Capitol with the poisoned berries.

- Return: Katniss emerges from the arena with Peeta.

- Change: She’s no longer just a hunter from District 12… she’s the face of rebellion.

Finding Nemo

- You: Marlin clings to the safety of his reef, overprotective of Nemo.

- Need: He wants to keep Nemo safe at all costs.

- Go: Nemo is captured, and Marlin must leave home to rescue him.

- Search: Marlin braves the open ocean, meeting Dory, sharks, and turtles.

- Find: He gets close to Nemo but faces setbacks along the way.

- Take: Marlin nearly loses Nemo for good and has to let go of his fear.

- Return: Father and son reunite and return home.

- Change: Marlin learns to trust and give Nemo freedom.

Die Hard

- You: John McClane arrives in LA, estranged from his wife.

- Need: He wants to repair his marriage.

- Go: Terrorists take over Nakatomi Plaza.

- Search: McClane sneaks through the building, taking out henchmen and gathering intel.

- Find: He rescues hostages but realizes Hans Gruber still holds the upper hand.

- Take: McClane suffers injuries and personal loss, but refuses to quit.

- Return: He confronts Gruber and saves Holly.

- Change: McClane is more than a cop now… he’s a man who fought for his family and won.

Common Mistakes With the Story Circle

The Story Circle is simple. That’s why people love it.

But “simple” doesn’t mean you can switch off your brain and coast. Here are a few places where writers trip themselves up:

- Treating it like IKEA instructions. Step 1, screw in bolt. Step 2, attach leg. No. If your story reads like you followed an assembly manual, readers will feel the gears grinding. Use the circle to guide, not to dictate.

- Chasing plot and ignoring the person. The character’s external goal is easy to show (grab the treasure, win the match, kiss the girl). But without a deeper need under it, the whole thing feels hollow. Readers don’t come back for the fireworks, they come back for the person in the middle of them.

- Lingering in the comfort zone. Writers love setup. Readers don’t. Show us just enough of the character’s normal life to feel the contrast when it shatters, then move on.

- Letting the middle meander. The “Search” step can be a dumping ground for aimless scenes. If the character isn’t moving closer to or farther from what they want, cut it. Wandering is fine for a hike, not for your story.

Bottom line: if you catch yourself bending your story to fit the circle instead of the circle bending to fit your story, you’re doing it backward.

The Story Circle vs. Other Frameworks

If you’ve spent any time around writing advice, you’ve seen a dozen different story models thrown at you. Three acts. Twelve steps. Fifteen beats. A pyramid. A curve.

It can feel like they’re competing. They’re not. They’re all different lenses for looking at the same thing.

Here’s how the Story Circle overlaps with the big story structures you often hear about, and where it does something different.

- The Fichtean Curve – This one is all rising action. The pressure never lets up. Great for thrillers, but not much room to show a character changing. The Circle gives you tension too, but with breathers and turning points baked in.

- The Three-Act Structure – Beginning, middle, end. Simple and useful. The Circle doesn’t replace it, it slides right inside. Act I is basically Steps 1–3, Act II is 4–6, Act III is 7–8.

- The Hero’s Journey – Campbell’s twelve steps, Vogler’s version for screenwriters… it’s mythic and inspiring, but also bloated. The Circle keeps the same “leave, struggle, return” DNA, just stripped down to eight steps you can actually remember.

- Freytag’s Pyramid – Exposition, rising action, climax, falling action, resolution. Looks good on a chalkboard. Less helpful when you’re drafting. The Circle is messier but more practical — it tells you what the character is doing, not just the slope of tension.

- The Five-Act Structure – Shakespeare’s favorite. Works for plays. Feels clunky for most modern fiction. The Circle lines up better with how today’s stories actually move.

- Save the Cat Beat Sheet – Snyder’s fifteen beats are fun to read and easy to spot in Hollywood films. But they’re very external. The Circle digs deeper into the character. Not just what happens, but what it costs them.

- The Snowflake Method – This isn’t a story shape at all. It’s an outlining trick. Good for blowing up an idea into a plan, but you still need something like the Circle to give it bones.

- The Seven Point Story Structure – Hook, plot turns, pinch points, midpoint, resolution. Handy checkpoints, but it doesn’t tell you how to flow between them. The Circle is more of a rhythm you can ride.

- The Story Spine – Pixar loves this one. “Once upon a time… Every day… Until one day…” Great for brainstorming, but it runs out of steam fast. The Circle carries you through a whole draft.

- In Medias Res – Not a structure. Just a way to start in the middle of the action. Gets attention, but you’ll still need a framework like the Circle to make the rest hang together.

How to Use the Dan Harmon Story Circle

Once you see it, you can’t unsee it.

The Story Circle shows up everywhere, from epic fantasy to romantic comedies to the quick stories we tell friends over coffee.

That’s the strength of Harmon’s framework. It’s simple, but it sticks, and it allows you to see the weak spots in your draft (or to make sure your character’s arc lands with impact).

BTW: If you want to map it out for yourself, we recommend using Plottr. It’s outlining software that works like digital notecards, letting you move pieces around without the mess of sticky notes on a wall. Plottr comes with the Dan Harmon Story Circle built in, so you can plug your story into the template and see the whole loop at a glance.

You don’t have to use a tool like Plottr to make the Story Circle work, of course.

Tool or no tool, it’s still one of the clearest ways to build a story that holds together.

—

An earlier version of this article was authored by Jason Hamilton. It has been rewritten and expanded for freshness and comprehensiveness.