Whether you meticulously outline every chapter or dive straight into the blank page, your novel still needs a story structure.

It’s the framework that holds everything together… the spine that keeps your narrative from collapsing into chaos.

But here’s the thing: there isn’t just one way to structure a story. Far from it. There are dozens of popular narrative structures, each with its own strengths, quirks, and fan base.

The trick isn’t hunting for the “perfect” formula. Focus instead on finding the framework that gives your story the most impact.

And in this guide, I'll help you do just that. We’ll break down 11 proven plot structures you can use to shape your novel.

Along the way, you’ll see why certain frameworks work better for different genres and get clear plot structure examples so you can decide which approach fits your writing style best.

- What narrative structure is

- 11 different story structures to experiment with

- When to use each story structure

What is Story Structure?

Story structure (sometimes called plot structure) is the framework that organizes all the events in your book into a deliberate, satisfying sequence.

Every story has a beginning, middle, and end. That’s the easy part. The challenge comes from deciding how to arrange those events. There are countless ways to get from page one to “The End,” but the best stories follow a clear, intentional path.

Using a strong story structure helps you do three things:

- Identify the most critical scenes to focus on.

- Cut unnecessary fluff that slows your pacing.

- Build a smoother, more compelling experience for the reader.

A novel structure isn’t there to box in your creativity. Think of it as a roadmap that helps your ideas land with more impact. And a well-planned roadmap can make the difference between “random collection of scenes” and a deliberate sequence of events that stick with your readers long after they close the book.

Basic Components of a Story

Most stories, no matter the genre, follow a basic plot structure made up of a few key elements:

- Exposition: Introduces the characters, setting, and premise.

- Inciting Incident: Kicks off the main conflict and forces the protagonist to act.

- Rising Action: Builds tension and raises the stakes, pulling readers deeper into the narrative.

- Climax: The turning point… the big showdown where everything comes to a head.

- Denouement: Resolves loose ends and shows how the events have changed the characters.

Mastering these components gives you a foundation to build richer, more satisfying story structures.

And once you’ve got the basics down, you can experiment with more advanced approaches. Below, we’ll explore 11 of the most popular plot structures (complete with examples) so you can find the framework that works best for your story:

- The Fichtean Curve

- The Three Act Structure

- The Hero's Journey

- Freytag's Pyramid

- The Five Act Structure

- Save the Cat Beats

- The Snowflake Method

- Dan Harmon's Story Circle

- The Seven Point Story Structure

- The Story Spine

- In Media Res

Let's jump right in.

1. The Fichtean Curve (Basic Story Structure)

The Fichtean Curve is one of the most fundamental plot structures in fiction. Think of it as the “default setting” for how most stories work: rising action, climax, and falling action.

(Picture a skewed triangle climbing upward… tension builds and builds until everything peaks, then resolves.)

The 3 Steps of the Fichtean Curve

- Rising Action: This makes up most of your story. It’s where the stakes keep climbing, crises stack on top of each other, and the protagonist gets pushed further out of their comfort zone. Each turning point fuels plot development and drives readers toward the inevitable showdown.

- The Climax: Everything comes to a head. Every threat, every secret, every choice converges at one high-stakes moment near the end of your novel. This is where tension hits its peak and your reader can’t look away.

- Falling Action: After the storm breaks, you give readers room to breathe. Loose ends are tied up, consequences play out, and the characters start finding their “new normal.”

When to Use the Fichtean Curve

Because it’s so foundational, this framework shows up everywhere.

Nearly all other story structures borrow from its core rhythm of rising action, climax, and falling action. You’ll see it in fantasy epics, thrillers, romances, and everything in between.

If you take nothing else from this guide, take this: no matter which advanced framework you choose later, mastering this basic plot structure first will make your writing stronger.

Skip these beats, and readers will feel like something’s missing (even if they can’t explain why).

Examples of the Fichtean Curve in Action

You’ll see this framework everywhere once you start looking. For example:

- The Hunger Games: Katniss faces escalating crises until the climactic showdown in the arena.

- The Martian: Mark Watney survives one life-threatening problem after another before finally escaping Mars.

- Die Hard: John McClane’s situation keeps getting worse until the explosive climax on the rooftop.

Once you start spotting this pattern in other stories, you’ll see how naturally it drives tension and keeps readers hooked.

2. The Three Act Structure

The three-act structure is everywhere. Hollywood has made it the backbone of modern storytelling, using it in nearly every blockbuster film. And once you start looking for it, you’ll see it show up in novels, plays, and TV shows too.

You’ll also notice that many of the other plot structures on this list borrow from this framework. It’s one of the most common types of plots you’ll encounter, which makes it worth mastering even if you plan to experiment later.

At its core, the three-act structure divides a story into a beginning, middle, and end, but each act breaks down into three steps, giving us nine total beats to work with.

The Nine Steps of the Three-Act Structure

Act I: Setup

- Exposition: Establish the “ordinary world” and introduce readers to your protagonist’s normal life.

- Inciting Incident: Drop the event that disrupts everything and kicks off the story.

- Plot Point 1: The protagonist commits to facing the conflict, crosses the “threshold,” and we move into Act II.

Act II: Confrontation

- Rising Action: The protagonist faces escalating challenges, each one raising the stakes.

- Midpoint: A major turning point flips everything upside down, making success feel almost impossible.

- Plot Point 2: After the midpoint, the protagonist suffers a major setback that forces them to question if they can succeed at all.

Act III: Resolution

- Pre-Climax: The protagonist regroups, refocuses, and prepares for the final confrontation.

- Climax: The ultimate showdown. The central conflict is resolved here — usually, but not always, in the protagonist’s favor.

- Dénouement: Loose ends are tied up, consequences play out, and the new status quo is revealed.

When to Use the Three-Act Structure

Because it’s so universal, this framework works across genres and mediums.

Whether you’re writing a romance novel, a mystery, or a sci-fi screenplay, it’s one of the most versatile story structures available.

That said, there are exceptions. If you’re writing a tragedy, for example, you might find the five-act structure or Freytag’s Pyramid more fitting.

But for most stories, this framework offers a reliable foundation to build on.

Examples of the Three-Act Structure in Action

- The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring : Frodo leaves the safety of the Shire (Act I), faces escalating dangers across Middle-earth (Act II), and reaches a climactic decision to continue the quest alone (Act III).

- The Wizard of Oz: Dorothy’s ordinary world is disrupted by a tornado (Act I), she faces mounting challenges in Oz (Act II), and ultimately defeats the Wicked Witch before returning home (Act III).

- Jurassic Park: The park opens (Act I), everything spirals out of control as the dinosaurs escape (Act II), and the survivors face a tense, high-stakes climax before escaping the island (Act III).

Watching how other stories pull off this framework gives you a roadmap. Not to copy, but to see why the pacing works and where the tension lands.

3. The Hero's Journey

The Hero’s Journey is one of the most recognizable forms of story structure (popularized by Joseph Campbell in The Hero with a Thousand Faces). Campbell studied myths from around the world and discovered a repeating pattern: a hero ventures out, faces trials, transforms, and returns changed.

Christopher Vogler later adapted Campbell’s work into a streamlined framework in The Writer’s Journey, breaking it into 12 steps that show up everywhere, from ancient epics to Hollywood blockbusters.

The 12 Steps of the Hero’s Journey

Part 1: Departure

- The Ordinary World: Establish the hero’s “normal” life before the adventure begins.

- The Call to Adventure: An inciting incident pushes the hero out of their comfort zone.

- Refusal of the Call: At first, the hero hesitates or resists the journey ahead.

- Meeting the Mentor: A guide appears, offering wisdom, tools, or inspiration to prepare the hero.

- Crossing the First Threshold: The hero fully commits and steps into the unknown, marking the start of the main plot.

Part 2: Initiation

- Tests, Allies, Enemies: The hero faces growing challenges, gains allies, and learns who they can’t trust.

- Approach to the Inmost Cave: The hero nears their goal, but uncertainty and danger loom large.

- The Ordeal: A critical, high-stakes confrontation forces the hero to face their deepest fears.

- Reward (Seizing the Sword): The hero earns a boon, insight, or advantage after overcoming the ordeal.

Part 3: The Return

- The Road Back: The hero sets out to return home, but the victory isn’t complete yet.

- Resurrection: The climactic challenge. Everything the hero has learned comes together in one final, defining moment.

- Return with the Elixir: The hero returns to the ordinary world, transformed, bringing new knowledge or strength with them.

When to Use the Hero’s Journey

This framework works beautifully for novel structures centered on transformation, growth, and self-discovery. While it’s most common in fantasy, science fiction, and superhero stories, it can apply to almost any genre.

Because, at the end of the day, every protagonist is the “hero” of their own narrative. Even in quieter dramas or character-driven tales, you can adapt these steps to suit your story and make it resonate on a mythic level.

Examples of the Hero’s Journey in Action

- Star Wars: A New Hope: Luke leaves Tatooine (Ordinary World), trains with Obi-Wan (Mentor), confronts Vader (Ordeal), and returns transformed as a Jedi-in-training.

- Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone: Harry discovers the wizarding world (Call to Adventure), faces escalating tests, and emerges victorious with newfound purpose and identity.

- Moana: Moana defies her limits, survives the ocean’s trials, and restores the heart of Te Fiti before returning home as a changed leader.

Study these examples carefully. The more you understand how this framework shapes character growth and pacing, the easier it becomes to bend the Hero’s Journey to your own storytelling needs.

4. Freytag's Pyramid

Freytag’s Pyramid is one of the oldest recognized story structures, dating back to the 1800s.

German novelist Gustav Freytag developed this framework after studying classical tragedies (think Shakespeare and other works that dominated literature at the time).

While some debate whether the pyramid includes five or seven steps, Freytag’s original model used five, so that’s the version we’ll focus on here.

The 5 Steps of Freytag’s Pyramid

- Exposition: Establish the status quo and introduce the world, characters, and central conflict. This phase typically ends with the inciting incident.

- Rising Action: Much like the Fichtean Curve, this is where tension builds, stakes rise, and the protagonist chases their goal while facing mounting obstacles.

- Climax: At the center of the story lies the turning point… the “point of no return” where everything pivots.

- Falling Action: Here, we see the fallout from the climax. In tragedies, this is often where the protagonist’s world begins to spiral out of control.

- Resolution (or Catastrophe): The conclusion, where the threads tie together. In classical tragedies, this often means the protagonist reaches their lowest point.

When to Use Freytag’s Pyramid

This framework shines when writing narrative structures inspired by classical literature, particularly tragedies.

While it’s less common in modern novels, it can be a powerful tool if you’re working on a story that calls for a slower build and a devastating emotional payoff.

Examples of Freytag’s Pyramid in Action

- Romeo and Juliet: We meet the feuding families (Exposition), follow their forbidden romance as tension escalates (Rising Action), hit the turning point when Tybalt is killed (Climax), watch the lovers’ situation spiral (Falling Action), and end in mutual tragedy (Resolution).

- Macbeth: Macbeth hears the witches’ prophecy (Exposition), climbs toward kingship through escalating bloodshed (Rising Action), reaches his point of no return after murdering Duncan (Climax), loses control as paranoia consumes him (Falling Action), and faces his ultimate downfall (Resolution).

- Death of a Salesman: Willy’s pursuit of the American Dream spirals into disillusionment, leading to a climax of personal despair and an inevitable tragic ending.

Freytag’s Pyramid won’t suit every project, but when you want to lean into themes of downfall, fate, or inevitability, it can give your plot structure a sharp edge.

5. The Five-Act Structure

The five-act structure is closely related to Freytag’s Pyramid (following the same core beats), but it’s a little more versatile.

Where Freytag focused on tragedies, this framework can handle a wider range of tones, including comedies and lighter narratives.

The 5 Steps of the Five-Act Structure

- Exposition: Establish the setting, introduce your characters, and set up the core premise.

- Rising Action: A chain of escalating events pushes the protagonist toward their goal while increasing tension.

- Climax: The turning point where everything collides, and there’s no going back.

- Falling Action: The ripple effects of the climax unfold as consequences catch up with the protagonist.

- Resolution (or Catastrophe): The story ties together, ending at the character’s highest triumph or deepest failure.

When to Use the Five-Act Structure

If you’re writing a story inspired by classical literature, this framework is worth exploring. Shakespeare used it not only for tragedies like Hamlet but also for comedies like A Midsummer Night’s Dream (proving you can use the same story structure to create very different emotional outcomes).

Examples of the Five-Act Structure in Action

- Hamlet: A classic five-act tragedy: Hamlet’s descent begins with grief (Exposition), spirals into vengeance (Rising Action), reaches the point of no return during the play-within-a-play (Climax), unravels in paranoia and bloodshed (Falling Action), and ends in tragedy (Resolution).

- A Midsummer Night’s Dream: Uses the same framework but flips the tone. Mistaken identities and chaos build (Rising Action), converge in magical entanglements (Climax), and settle into comedic resolution as the lovers reunite.

- Pride and Prejudice: While more subtle, Austen’s novel still echoes this rhythm: misunderstandings mount (Rising Action), Darcy’s first proposal lands at the midpoint (Climax), and reconciliation brings everything full circle (Resolution).

Studying how different genres use this same framework helps you see how adaptable it can be (and how you can tailor it to match the emotional core of your own story).

6. Save the Cat Beats

The Save the Cat framework was created by screenwriter Blake Snyder and has become one of the most widely used story structures in modern storytelling.

Originally designed for screenplays, Snyder’s method maps out 15 “beats” (ie, key turning points that keep a story moving and readers invested).

While the original Save the Cat beat sheet includes suggested page counts for each beat in a screenplay, novelists can adapt the formula just as easily. The beats themselves matter more than the pacing guidelines, making this one of the most flexible frameworks for writers.

The 15 Steps of the Save the Cat Formula

- Opening Image: A snapshot that sets the tone, mood, and feel of the story while giving us an early look at the protagonist.

- Setup: Introduce the world, establish relationships, and give us a reason to care about what happens next.

- Theme Stated: Somewhere in the setup, hint at the deeper message or lesson your story will explore.

- Catalyst: The inciting incident. Something happens that kicks the story into motion.

- Debate: The protagonist hesitates, questions their path, or even refuses the journey ahead.

- Break into Two: The leap into Act II, where the hero commits fully to the central goal.

- B Story: A subplot emerges, often involving romance, friendship, or another emotional thread.

- Fun and Games: The “promise of the premise.” The hero experiments with their new world or role before the stakes get serious.

- Midpoint: A major twist or revelation changes the trajectory of the story entirely.

- Bad Guys Close In: Tension ramps up as obstacles, enemies, or doubts surround the protagonist.

- All Is Lost: A crushing setback forces the hero to confront their deepest fears.

- Dark Night of the Soul: The hero hits rock bottom, questioning everything before the final push.

- Break into Three: A new insight or revelation sparks a path forward into Act III.

- Finale: The climax. The hero uses everything they’ve learned to confront the antagonist or central challenge.

- Final Image: A closing snapshot that mirrors the opening image, showing just how much the hero has transformed.

When to Use Save the Cat

This framework is perfect if you want clear, actionable beats to guide your plot development. While it was designed for film and TV, novelists can adapt the steps easily by focusing on the emotional shifts rather than Snyder’s suggested page counts.

Whether you’re writing a fast-paced thriller, a heartfelt romance, or an epic fantasy, these beats can give your plot structure a strong backbone without feeling restrictive.

Examples of Save the Cat in Action

- Legally Blonde: Elle’s “Opening Image” contrasts her sorority world with Harvard Law, and her “Final Image” mirrors her growth into someone who owns both identities.

- Finding Nemo: Marlin’s world is shattered by loss (Catalyst), he hesitates to leave the reef (Debate), faces escalating challenges (Bad Guys Close In), and transforms into a braver, more open father (Finale).

- The Hunger Games: Katniss volunteers as tribute (Catalyst), adapts to the Capitol (Fun and Games), faces Rue’s death (All Is Lost), and emerges as a reluctant symbol of rebellion (Final Image).

Watching how other stories hit these beats helps you understand why they work and how you can adapt them to create momentum and emotional payoff in your own writing.

7. The Snowflake Method

The Snowflake Method, developed by Randy Ingermanson, takes a different approach to planning your story.

Instead of starting with a rigid story structure, it uses expansion as a metaphor: you begin with a single, simple idea and build outward (step by step) until you have a fully fleshed-out narrative.

The name comes from the Koch Snowflake, a fractal that starts as a simple triangle but becomes increasingly complex as you add more layers.

The same principle applies here: start small, then expand gradually until your plot structure is fully formed.

The 10 Steps of the Snowflake Method

- Craft a One-Sentence Summary: Boil your story down to its essence. If you can’t describe it in one sentence, your core idea isn’t sharp enough yet.

- Write a One-Paragraph Summary: Expand the single sentence into a short overview of your plot.

- Create Character Synopses: Outline your main characters, their goals, and motivations.

- Grow Your Story to a One-Page Description: Expand the paragraph into a single page that covers the major beats of your narrative.

- Review and Refine Character Descriptions: Deepen your character backstories as your plot takes shape.

- Create a Four-Page Plot Outline: Build a more detailed roadmap of the story’s events.

- Develop Full Character Charts: Flesh out your characters’ histories, arcs, and relationships.

- Break Down Story Scenes: Identify the individual scenes that will bring your plot to life.

- Sketch Out Chapters: Combine your scenes into a chapter-by-chapter outline.

- Write the First Draft: With everything planned, it’s time to put words on the page.

When to Use the Snowflake Method

Unlike some of the other frameworks, this is less about prescribing a specific story structure and more about guiding your creative process. It’s ideal for writers who feel overwhelmed by the idea of plotting or aren’t sure where to start.

By beginning small and expanding in stages, the Snowflake Method helps you stay true to your story’s core while developing characters, scenes, and subplots in a natural, deliberate way.

Examples of the Snowflake Method in Action

- The Da Vinci Code (Dan Brown): A tightly woven thriller that benefits from meticulous planning at both the scene and chapter levels.

- Outlander (Diana Gabaldon): With multiple timelines, layered character arcs, and intertwined subplots, this series exemplifies the method’s “start simple, build complexity” philosophy.

- Mistborn (Brandon Sanderson): Complex worldbuilding paired with carefully structured payoffs demonstrates how incremental plotting creates major narrative impact.

If you thrive on structure but hate feeling boxed in, the Snowflake Method gives you the best of both worlds: a framework for organization and the freedom to develop your ideas step by step.

8. Dan Harmon's Story Circle

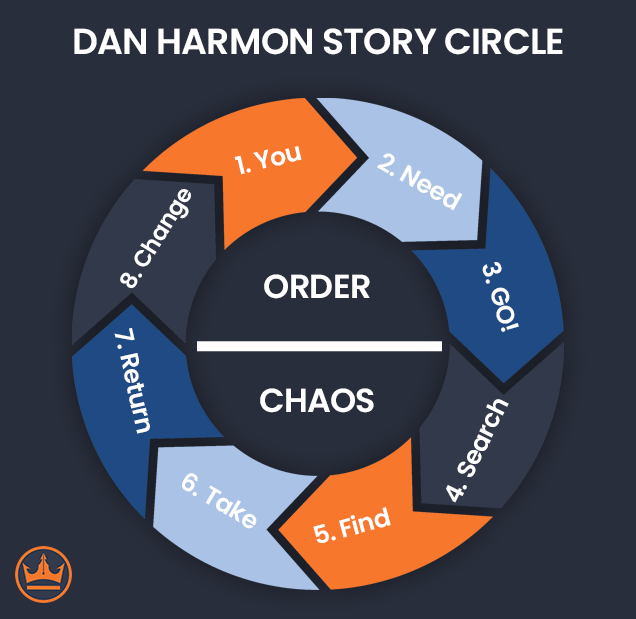

Screenwriter Dan Harmon (best known as the creator of Community and co-creator of Rick and Morty) developed the Story Circle as a streamlined alternative to the Hero’s Journey.

Where Campbell’s model often emphasizes myth and scope, Harmon’s approach zeroes in on character arcs. It’s less about world-shaking events and more about what the protagonist wants, what they risk to get it, and how they change in the process.

The Eight Steps of Dan Harmon’s Story Circle

- You: Start by grounding the character in their “zone of comfort.”

- Need: Establish what they want or what’s missing in their life.

- Go: The character enters an unfamiliar situation to chase that desire.

- Search: They adapt, experiment, and learn to survive in this new world.

- Find: The character gets what they were after… or thinks they do.

- Take: There’s a cost. Achieving the goal comes with sacrifice or consequence.

- Return: The character goes back to where they started, but they’re not the same.

- Change: By the end, the journey transforms who they are and how they see the world.

When to Use Dan Harmon’s Story Circle

The Story Circle is ideal if you want a Hero’s Journey-style narrative but prefer to focus on character growth rather than sweeping, mythic stakes. It’s especially useful for writers who want a clear, adaptable framework for designing arcs where transformation is front and center.

Because change is at the heart of good storytelling, this model works for a wide range of plot types (from intimate dramas to fast-paced sci-fi adventures).

Examples of Dan Harmon’s Story Circle in Action

- Rick and Morty: Harmon uses his own framework to structure episodes, with characters regularly leaving their comfort zones, facing consequences, and returning changed.

- The Lion King: Simba flees his home (Go), builds a new life (Search), confronts Scar (Take), and returns to Pride Rock transformed (Change).

- Inside Out: Joy learns to adapt in an unfamiliar world, faces personal sacrifices, and returns with a deeper understanding of herself and Riley’s emotions.

If you want a plotting framework that balances story momentum with emotional depth, Harmon’s Story Circle offers a clean, character-focused way to do it.

9. Seven-Point Story Structure

The Seven-Point Story Structure is a simple but powerful story framework that breaks your narrative into seven key milestones. It’s a great way to plan stories because it offers clear direction without boxing you in.

Like several other frameworks on this list, it builds on the familiar three-act structure but approaches it from a fresh angle. Instead of thinking in terms of “acts,” you focus on the turning points that give your narrative arc its shape.

The 7 Steps of the Seven-Point Story Structure

- Hook: Start by grounding readers in the protagonist’s world while introducing a spark of intrigue to draw them in.

- Plot Point One: The inciting incident disrupts normal life and pushes the protagonist into unfamiliar territory.

- Pinch Point One: The first real clash with the antagonist forces the protagonist to confront what’s truly at stake.

- Midpoint: A major shift in perspective. The protagonist takes full responsibility and starts driving the story forward.

- Pinch Point Two: Conflict deepens, hope fades, and the protagonist hits their lowest moment.

- Plot Point Two: A breakthrough: the hero gains new information, tools, or allies that change everything.

- Resolution: The climax and conclusion. The protagonist’s journey reaches its peak, for better or worse.

When to Use the Seven-Point Story Structure

This model is particularly useful for discovery writers (those who prefer “writing into the dark” rather than meticulously outlining). It gives you seven major milestones to aim for without forcing you to map out every beat in advance.

That said, its flexibility also makes it a solid choice for planners. Whether you outline heavily or lightly, these checkpoints can strengthen your story’s pacing and provide a dependable skeleton to build on.

Examples of the Seven-Point Story Structure in Action

- The Hunger Games: Katniss’s “hook” introduces life in District 12, “plot point one” begins when she volunteers as tribute, and “pinch points” highlight escalating conflicts until the arena’s final resolution.

- The Matrix: Neo’s call to adventure begins with Morpheus’s offer (plot point one), his first clash with Agents raises the stakes (pinch point one), and the climax resolves his transformation into “The One.”

- The Fault in Our Stars: The hook introduces Hazel’s quiet, sheltered life, the midpoint revolves around her emotional awakening with Augustus, and the final resolution balances heartbreak with growth.

For writers who want a simple plotting framework that delivers structure without rigidity, the Seven-Point Story Structure offers a clean, approachable way to shape a satisfying narrative.

10. Story Spine

The Story Spine is a simple, flexible storytelling model popularized by Pixar. It distills a narrative into seven intuitive beats that focus on cause-and-effect rather than rigid plotting.

If you’ve read the other frameworks on this list, some of these steps will feel familiar, but the Story Spine phrases them differently, making it especially approachable for new writers.

The Seven Steps of the Story Spine

- Once Upon a Time… – Establish the protagonist’s starting situation.

- And Every Day… – Show what “normal” looks like in their world.

- Until One Day… – The inciting incident arrives and shakes everything up.

- And Because of This… – The character takes action, leaving their comfort zone.

- And Because of This… – One choice leads to another, creating a chain of consequences and complications.

- Until Finally… – The climax: the final turning point where the central conflict comes to a head.

- And Ever Since That Day… – Reveal how the journey has changed the protagonist and shaped their new “normal.”

When to Use the Story Spine

If you like discovery writing but still want some structure, this narrative pattern is a great fit. It gives you a roadmap without locking you into a rigid outline, making it especially useful for writers who prefer freedom while drafting.

Because it’s so streamlined, the Story Spine also works well for shorter formats (like picture books, short stories, or even flash fiction) while still being adaptable for full-length novels.

Examples of the Story Spine in Action

- Finding Nemo: “Once upon a time,” Marlin lives a quiet life on the reef. “Until one day,” Nemo is captured, sending Marlin on a chain of escalating choices that culminate in their reunion.

- Toy Story: Woody’s jealousy of Buzz sets off a domino effect of choices and consequences that eventually resolve in the climactic rescue and new friendship.

- Up: Carl clings to his old life “every day” until Ellie’s death (Until One Day). Each decision he makes to honor her pushes him deeper into change, leading to the emotional transformation at the story’s end.

For writers who want a framework that focuses on cause-and-effect rather than heavy outlining, the Story Spine delivers clarity without complexity.

11. In Medias Res

In Medias Res (Latin for “in the middle of things”) is less a rigid story structure and more a storytelling technique.

The idea is simple:

Start your narrative right in the heat of conflict. No warm-up. No lengthy setup. You drop the reader straight into the action and let them catch up along the way.

Think of Star Wars: A New Hope. The movie opens mid-battle, in the middle of a war between the Rebels and the Empire. We don’t know who’s winning, who’s losing, or why it matters, and that mystery hooks us immediately.

The Six Steps of In Medias Res

- In Medias Res: Begin in the thick of things, skipping lengthy exposition.

- Rising Action: As the tension escalates, readers learn more by watching the characters adapt and react.

- Explanation: Sprinkle in backstory and context at natural “breathing points” to keep readers oriented without slowing the pace.

- Climax: Everything collides at the high point of the story, where the outcome hangs in the balance.

- Falling Action: After the climax, loose ends start tying up and the tension eases.

- Resolution: Characters return to a new normal, with remaining threads addressed.

When to Use In Medias Res

This narrative approach works when you want to hook readers fast. It’s especially effective for thrillers, mysteries, and action-heavy genres, but you’ll also find it used in dramas and literary fiction to create instant engagement.

That said, starting mid-action doesn’t always mean beginning at your inciting incident. Sometimes, you open on a smaller moment of tension that plants intrigue, then layer in stakes as you go.

Whatever route you take, the goal is the same: pull readers into your story immediately and give them a reason to turn the page.

Examples of In Medias Res in Action

- Mad Max: Fury Road: Opens mid-chase with zero setup, teaching us about the world through the chaos itself.

- The Odyssey: One of the earliest examples: we meet Odysseus mid-journey, piecing together his trials from fragments of backstory.

- The Dark Knight: Drops us straight into the Joker’s bank heist, pulling us into the story before we know the players or the stakes.

For writers who want their stories to start with urgency and momentum, In Medias Res offers a fast lane into reader engagement.

Wrapping Up Your Story’s Structure

No matter which framework you choose…

Whether it’s the detailed beats of Save the Cat, the clean milestones of the Seven-Point Story Structure, or the chaos-first approach of In Medias Res…

The goal is the same: to give your story momentum, clarity, and emotional impact.

You don’t have to follow any one system perfectly. In fact, many writers blend ideas from multiple frameworks until they find a rhythm that feels natural. The best story structure isn’t the one that’s trendy or prescriptive. It’s the one that helps you tell your story in the strongest possible way.

So experiment.

Borrow what works.

Bend or even break the “rules” when your gut tells you to. Because these frameworks aren’t cages. They’re tools you can shape to fit the story you want to tell.

And the more tools you understand, the more freedom you have to create something unforgettable.

—

An earlier version of this article was authored by Jason Hamilton. It has been rewritten and expanded for freshness and comprehensiveness.