A lot of people want to write a book. Most never get to the end of one.

I’ve watched it happen for years. Someone has an idea they’re excited about. They talk about it. They think about it. They read advice and look for the right moment to begin. Weeks pass. Then months. At some point, the idea starts to feel heavier than it did at the beginning.

Writing stays on the to-do list, but it never becomes part of the routine.

The problem usually shows up early. People don’t know what they should focus on first, so everything feels equally important. That makes it hard to take action without second-guessing every choice. When progress feels uncertain, it’s easier to pause than to push forward.

This article is about that phase.

It’s meant to help you turn writing from something you plan to do into something you actually sit down and work on. The focus here is on the early decisions that determine whether writing becomes something you return to or something that quietly slips away.

Who Am I to Teach You How to Write a Book?

I’ve written more than a dozen books over the years, and several of them have reached bestseller lists.

I’ve also worked closely with authors in different genres, helped publishing companies behind the scenes, and coached writers who were stuck partway through projects they wanted to finish.

I’ve spent a lot of time watching where things break down.

The same issues come up again and again. Writers start with energy, then lose momentum. They change tools too often. They keep adjusting plans instead of writing. Small obstacles turn into reasons to stop for long stretches of time.

The people who finish books usually approach the beginning in a more practical way. They simplify things early. They make writing easier to return to. They don’t wait for ideal conditions.

Everything in this guide comes from seeing what helps writers keep going once the novelty wears off.

The point here isn’t to turn writing into a system or overwhelm you with rules. It’s to help you start in a way that supports the work instead of quietly working against it.

Let’s get started.

Step 1: Establish Your Writing Space

Where you write matters more than most people expect.

This doesn’t mean you need a perfect office, expensive furniture, or a room with a door that locks. It means you need a place where writing can happen without friction. When the space works against you, writing becomes something you avoid instead of something you return to.

I’ve written in everything from dedicated offices to borrowed kitchen tables. The setup itself didn’t matter much. What mattered was how easy it felt to sit down and begin.

I’ve seen plenty of writers stall because every session starts with small obstacles. They sit down, then realize they don’t have what they need. The chair is uncomfortable. The desk is cluttered. The environment reminds them of everything except the book they’re trying to write.

Those little delays add up.

Your writing space should remove decisions, not create them. When you sit down, the goal is to start writing within a minute or two, not reorganize, troubleshoot, or negotiate with yourself.

That space can look different for different people. For some, it’s a desk at home that’s used only for writing. For others, it’s a specific seat at a coffee shop or a corner of the house that signals “this is where writing happens.” The common thread is consistency.

Once your brain starts to associate a place with writing, getting started becomes easier. You don’t have to warm up as much. You don’t have to convince yourself. The environment does some of the work for you.

A simple rule helps here: your writing space should make writing the easiest thing to do in that moment. Fewer distractions. Fewer setup steps. Fewer excuses to delay.

Perfection isn’t the goal here. The space only needs to work well enough that sitting down doesn’t feel like a hurdle.

Once that’s in place, the next step is choosing tools that support the work instead of getting in the way.

Step 2: Establish Your Writing Tools

The tools you choose won’t write the book for you, but the wrong ones can slow you down more than you realize.

A lot of new writers bounce between apps early on. They draft in one place, take notes somewhere else, then start thinking about formatting long before the manuscript is finished. That back-and-forth creates friction. Writing starts to feel fragmented instead of focused.

The best writing tools do one simple thing well. They make it easier to keep your work in one place and return to it consistently.

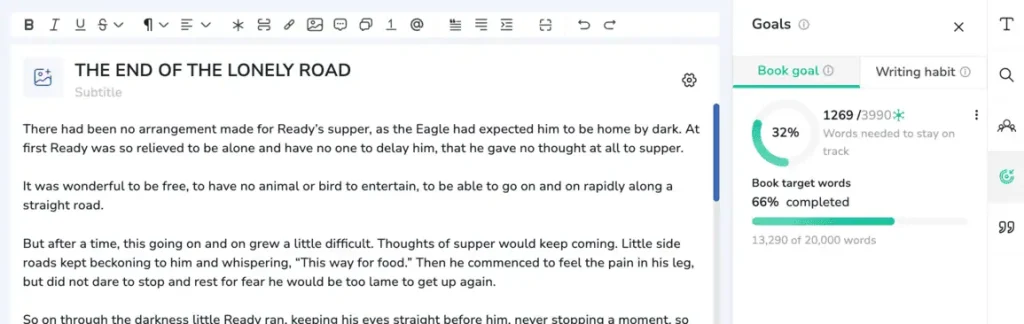

For most authors, that’s where Atticus makes sense. It lets you write from any device, keeps your manuscript organized, and handles formatting later when the book is ready. You don’t have to rethink your setup halfway through the project or move your draft into new software just to prepare it for publishing.

That alone removes a common point where books stall.

Many writers reach the end of a draft and then realize they need to migrate everything into a different tool. That transition often leads to delays or unfinished revisions. Using software that supports both drafting and formatting avoids that problem.

Other tools can still support the process, as long as they stay in a supporting role.

Some authors use editors like ProWritingAid or AutoCrit to review drafts after the writing session is over. These tools can help spot patterns, pacing issues, or clarity problems once the words are already on the page.

Fiction writers sometimes experiment with tools like Sudowrite to explore ideas or work through stuck scenes. Used carefully, tools like this can help with momentum, as long as they don’t replace the actual writing.

Some writers also prefer drafting environments like Scrivener, especially for complex projects. The key is choosing something that fits how you think and write, not what feels impressive or feature-rich.

What matters most is predictability. If your tools feel familiar and easy to open, writing becomes easier to return to. That consistency matters far more than having the “perfect” setup.

Once your tools are in place, the next step is deciding when the writing actually happens.

Step 3: Set a Writing Schedule (and Protect It)

A book tends to stall when writing keeps getting pushed aside during the week.

A lot of people wait until they feel ready to write. They look for long stretches of free time or the right mental state. In real life, that approach rarely works. Days fill up. Energy shifts. Writing keeps getting pushed to tomorrow.

Authors who finish books treat writing like a commitment, not a mood.

That doesn’t mean you need hours every day. It means you decide when writing happens and defend that time from everything else that tries to take it over. Once it’s on the calendar, the decision is already made. You show up and work with whatever energy you have.

This is where tools can help reinforce the habit. In Atticus, you can set word count goals and track progress over time, which gives you a clear sense of momentum instead of guessing how far along you are.

The numbers aren’t there to pressure you. They give structure to the work. When you know what you’re aiming for in a session, it’s easier to start and easier to stop without feeling lost.

Writing on a schedule also changes how you deal with resistance. Writer’s block still shows up, but it doesn’t get to decide whether you write that day. Some sessions will feel productive. Others won’t. Both still count.

The goal is regular contact with the manuscript. Small, consistent progress adds up faster than occasional bursts of effort.

Once writing becomes part of your routine, the work stops feeling fragile. That’s when finishing starts to feel realistic.

Next, we’ll talk about something many writers skip too late in the process: making sure the book they’re working on is worth the time they’re investing.

Step 4: Validate Your Book Idea Before You Go Too Far

This is the step many writers skip, then wish they hadn’t.

Once you start writing, it’s easy to fall in love with the project. Time goes in. Effort goes in. Momentum builds. That makes it harder to step back and ask whether the idea itself is worth the investment.

Validation is about answering that question early.

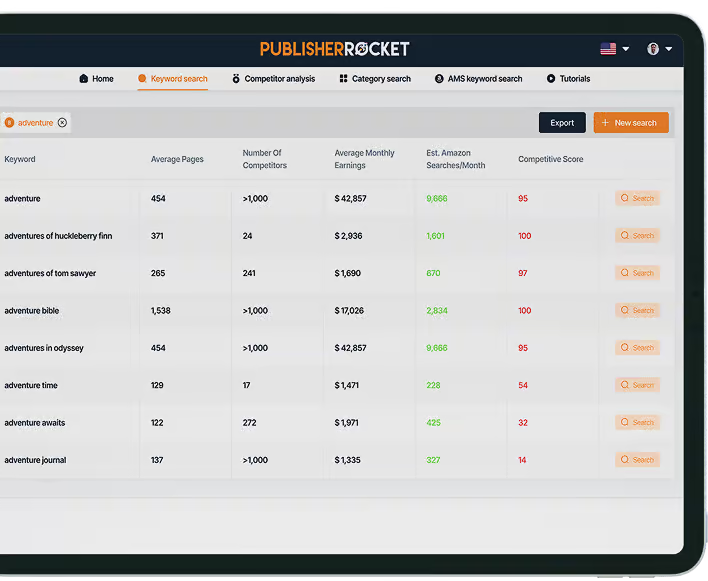

If your goal is to publish and reach readers, it helps to know there’s real interest in the topic before you spend months writing the book. A simple validation check can reveal whether people are already looking for books like yours, how competitive the space is, and where your idea fits.

This doesn’t need to turn into a research marathon. You’re not trying to predict sales with precision. You’re looking for signals that the idea has an audience and that you’re not walking into a dead end.

I’ve seen plenty of writers pour energy into projects that were difficult to position from the start. By the time they realized it, the manuscript was finished and enthusiasm had worn thin. A small amount of validation up front would have changed the direction of the book or saved months of work.

If you want a deeper walkthrough of this process, check out our guide to book idea validation that covers how to check demand, competition, and positioning without getting stuck in analysis. It’s worth reading before you go much further.

Once you’re confident the idea is solid, outlining and writing become much easier to commit to. You’re no longer guessing whether the work is worthwhile. You’re building toward something with a clearer purpose.

Next, we’ll talk about creating an outline that gives you direction without turning the process into busywork.

Step 5: Develop a Simple Outline

An outline gives your writing direction.

Without one, it’s easy to sit down, stare at the page, and wonder what you’re supposed to work on that day. That uncertainty slows everything down. Writing starts to feel heavier because every session begins with figuring out what comes next.

An outline doesn’t need to be detailed. It doesn’t need to lock you into a rigid plan. It just needs to give you a path forward so you’re not making structural decisions while trying to write.

For many authors, a simple “skeleton” outline works best. That might be a list of chapters or sections, with a few notes under each one about what needs to be covered. Enough structure to guide the session. Enough flexibility to adjust as the book takes shape.

Outlining becomes a problem when it turns into avoidance. Some writers keep revising their outline instead of moving into the manuscript. Others try to plan every paragraph before writing a single page. That level of detail usually slows progress rather than helping it.

The goal here is clarity, not control.

When you know what you’re working on next, starting a session feels easier. You spend less time second-guessing and more time writing. The outline becomes something you return to briefly, not something you manage constantly.

If tools help you think through structure, a few options are worth considering:

- Plottr — Useful for visual thinkers who like seeing the book laid out by sections or plot points.

- Scrivener — Offers corkboard-style outlining for writers who prefer a flexible, movable structure.

- Atticus — Lets you outline directly inside the manuscript, keeping planning and writing in one place.

Use whichever approach helps you sit down and keep going. The outline should support the writing, not become the work itself.

Once you have a clear structure, it becomes easier to think about pace and progress. That’s where goals and word counts come in.

Step 6: Set Word Count Goals (Without Getting Lost in Research)

Goals give your writing sessions shape.

Without them, it’s easy to drift. You might open the document, reread what you wrote last time, tweak a sentence or two, then stop without moving the book forward. That kind of session feels busy, but it doesn’t build momentum.

A word count goal gives you a clear stopping point. You know when the session is done, and you know whether progress happened. That clarity makes it easier to show up again the next time.

The exact number matters less than consistency. Some writers aim for a few hundred words. Others write more when time allows. What works is choosing a target that fits your schedule and treating it as a guideline rather than a test.

Research can complicate this step.

It’s easy to justify time spent reading, outlining, or gathering sources, especially early in the process. Research feels productive, and sometimes it is. The problem shows up when research starts replacing writing. I’ve seen writers stay in that mode for months and still have very little on the page.

A simple rule helps here. Separate research time from writing time. When the session is meant for writing, write. Make a note of questions that come up and deal with them later. That keeps the manuscript moving instead of stalling in preparation.

Progress builds confidence. Confidence makes it easier to return. Word count goals support that loop by giving each session a clear purpose.

Once writing starts to accumulate, the next challenge is showing up regularly, even when the work feels slow or uncomfortable.

Step 7: Get to Your Book Daily

Finishing a book depends less on how any single session goes and more on how often you return to the work.

Some days will feel productive. Others won’t. That’s normal. The problem starts when uneven sessions turn into long gaps. Once too much distance builds up, restarting feels harder than continuing ever did.

Daily contact with the manuscript keeps that distance from forming.

That doesn’t mean you need to write thousands of words every day. It means you open the document and engage with the book in some way. You might write. You might revise a section you flagged earlier. You might add notes for the next chapter. The key is staying connected.

Momentum comes from familiarity. When the book is part of your routine, it stays mentally accessible. You don’t have to reorient yourself every time you sit down. The story or argument stays close enough that progress feels possible, even on days when energy is low.

This is also where many writers get tripped up by expectations. They assume every session needs to feel meaningful. In reality, some days exist simply to keep the chain unbroken. Those days still matter. They prevent the book from slipping back into the abstract.

Getting to the manuscript regularly builds trust with yourself. Over time, that trust matters more than motivation. You stop negotiating about whether you’ll write and start treating it as something you already do.

Once that habit is in place, the rest of the process becomes easier to manage. Writing feels less fragile. The book starts to feel real.

Need Help Writing and Publishing Your Book?

Writing a book is only part of the process.

Once the draft exists, new questions show up. Editing. Formatting. Publishing decisions. Marketing. Each stage comes with its own learning curve, and it’s easy to feel unsure about what to tackle next or how much time to spend on any one step.

If you want guidance beyond this article, that’s where the Authorpreneur Academy can help.

Its designed to walk authors through the full path, from writing to publishing to getting the book in front of readers. It covers the steps in order, explains what actually matters at each stage, and helps you avoid the common mistakes that slow people down or send them in the wrong direction.

Some writers prefer to figure things out on their own. Others want a clearer framework and fewer unknowns. If you’re in the second group, having everything laid out in one place can save a lot of time and frustration.

Either way, the most important thing is continuing to move forward.

Bookmark this guide and come back to it as you work.

Writing a book isn’t a single decision. It’s a series of small ones made over time. The more consistently you show up, the more real the project becomes.