Every writer’s been there.

You’ve got a great premise, strong characters… and then your story stalls halfway through. Scenes wander. Stakes fade. You start wondering if you’re missing some secret formula everyone else knows.

That’s where the Save the Cat Beat Sheet comes in. Created by screenwriter Blake Snyder, this 15-step framework has helped thousands of authors and filmmakers fix sagging middles, sharpen turning points, and keep readers hooked from page one to “The End.”

- What the Save the Cat beat sheet is

- The origins of Save the Cat

- A beat-by-beat breakdown of each step

By the time you’re done, you’ll have a proven roadmap for shaping your draft… without feeling boxed in by someone else’s rules.

The Origins of the Save The Cat Beat Sheet

The Save the Cat Beat Sheet was created by the late Blake Snyder, a Hollywood screenwriter best known for the 1994 Disney movie Blank Check and several episodes of Kids Incorporated.

In 2005, Snyder published Save the Cat! The Last Book on Screenwriting You’ll Ever Need, a guide that quickly became one of the most popular resources for storytellers. It’s still in print today, with dozens of reprints and spin-offs focused on both screenwriting and novel writing.

The name comes from a simple idea Snyder loved to teach:

If you want your audience to root for your protagonist, show them doing something that earns empathy… like, quite literally, saving a cat.

The concept was inspired by a moment in James Cameron’s Aliens, where Ripley risks her life to save her cat, Jonesy, from a deadly xenomorph. In one beat, the audience connects with her on a human level (and they stay invested for the rest of the story).

You see the same principle in Disney's original Aladdin (1992), when Aladdin risks punishment to give his stolen bread to two starving children.

That single choice signals to the audience that, despite his flaws, he’s someone worth caring about.

Get it for FREE here:

What is The Blake Snyder Beat Sheet?

At its core, the Blake Snyder Beat Sheet is an expansion of the classic three-act story structure. It breaks a story into 15 key “beats” (moments of change that keep the plot moving and the audience engaged).

If you diagram it, the structure looks a little like a skewed pyramid: exposition and setup at the base, rising tension as the stakes climb, a peak at the climax, and a downward path toward resolution.

(You’ll see what I mean in the image below.)

Every story that uses this framework is character-driven.

There’s always a hero (or anti-hero) whose mission is blocked by an opposing force. At the Midpoint, the ground usually shifts beneath them (a major twist forces the protagonist to see the fight ahead more clearly, often for the first time). From there, the tension builds until the final act delivers either victory or catastrophe.

You can see this in the original Jurassic Park. The Midpoint comes when the T. rex escapes its paddock… a twist that changes the entire trajectory of the story. What had been a controlled, awe-inspiring environment instantly becomes a fight for survival.

The same thing happens in The Hunger Games. At the Midpoint, Katniss forms an alliance with Rue, and together they destroy the Careers’ food supply. It’s a turning point that forces Katniss to rethink her strategy and raises the stakes for everyone left in the arena.

Blake Snyder designed the beat sheet to help writers master scene timing and plot placement.

Where does your inciting incident go? When should your character hit rock bottom? How long can you build tension before you need a payoff?

The framework helps you answer those questions without boxing in your creativity.

A Quick Summary of Blake Snyder's Save the Cat Beat Sheet

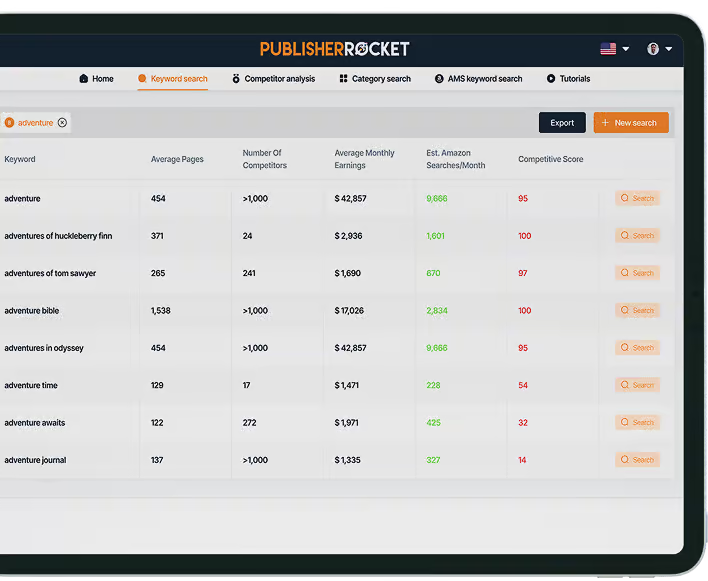

If you just want the highlights, here’s the entire Save the Cat Beat Sheet at a glance. These are the 15 key beats and the role each one plays in shaping your story:

| Beat | % of Story | Purpose | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Opening Image | 0-1% | Snapshot of the hero’s “before” world. | The Martian – Mark jokes about being stranded. |

| Theme Stated | ~5% | Quietly hints at the story’s deeper truth. | To Kill a Mockingbird – Atticus’s empathy lesson. |

| Set-Up | 1-10% | Introduces the hero, stakes, flaws, and supporting cast. | Finding Nemo – Marlin’s overprotectiveness. |

| Catalyst | ~10% | The inciting incident that changes everything. | The Lion King – Mufasa’s death. |

| Debate | 10-20% | Hero hesitates, wrestling with doubts or fear. | Moana – doubts her ability to sail beyond the reef. |

| Break Into Two | 20% | Hero commits to change, entering a “new world.” | Narnia – Lucy and siblings step through the wardrobe. |

| B Story | ~22% | Secondary plotline deepens the theme, often via relationships. | Good Will Hunting – Will’s therapy sessions. |

| Fun and Games | 20-50% | The “promise of the premise” (exploring the story’s hook). | Charlie and the Chocolate Factory – magical factory tour. |

| Midpoint | 50% | Major twist: false victory, false defeat, or raised stakes. | Titanic – the iceberg strike changes everything. |

| Bad Guys Close In | 50-75% | External threats and internal doubts collide. | The Empire Strikes Back – Luke and friends under siege. |

| All Is Lost | ~75% | Something “dies” (literally or figuratively) and hope fades. | The Fault in Our Stars – Augustus reveals his relapse. |

| Dark Night of the Soul | 75-80% | Hero reflects, grieves, and faces who they must become. | Inside Out – Joy realizes sadness has value. |

| Break Into Three | ~80% | Epiphany sparks renewed resolve heading into Act III. | Mulan – spots the Huns heading to the Imperial Palace. |

| Finale | 80-99% | Climax (protagonist applies what they’ve learned to confront the conflict). | The Return of the King – Frodo destroys the Ring. |

| Final Image | 99-100% | Mirrors the Opening Image, showing transformation. | Shawshank Redemption – Red walks free on the beach. |

(Quick Tip: If you want an easy way to visualize these beats, I recommend Plottr, a plotting tool for authors that incorporates Save the Cat and many other narrative structures.)

The Save the Cat Story Structure: A Beat-by-Beat Breakdown

The quick summary gave you the highlights. Now it’s time to go deeper.

In this section, we’ll walk through all 15 beats of the Save the Cat Beat Sheet in detail… what each one accomplishes, where it fits into your story, and how successful books and movies have used it.

By the end, you’ll have a clear sense of how the beats work together to create pacing, tension, and emotional payoff (and you'll know how to adapt them to your own story).

Beat #1: Opening Image (0-1%)

Your story’s first impression.

In a single scene or paragraph, you’re showing readers who your protagonist is before everything changes. It’s a snapshot of their ordinary world, their personality, and what’s missing from their life (without spelling it out directly).

The key is to make it visual and memorable. You’re setting the emotional baseline so readers can see just how far the character will grow once the story unfolds.

Examples:

- In The Martian by Andy Weir, Mark Watney casually explains how he became stranded on Mars. His humor sets the tone, but we also glimpse his isolation.

- In Pixar's Up, the silent montage of Carl and Ellie’s life together establishes everything about Carl’s personality and the loss he carries into the rest of the story.

Done well, the opening image plants a quiet promise: “Here’s where we start. Watch how far we’ll go.”

Beat #2: Theme Stated (5%)

Within the first few pages or minutes, your story quietly hints at its big idea: the deeper truth your protagonist will wrestle with and eventually learn.

The key word here is hint.

You don’t announce the theme in bold letters. Instead, it usually slips into the story naturally, often as a line of dialogue, a brief moment, or a small interaction that lands differently once you know where the story goes.

Examples:

- In To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee, Atticus Finch tells Scout, “You never really understand a person until you consider things from his point of view.” That single line quietly sets up the book’s central lesson about empathy and justice.

- In The Matrix (1999), Morpheus tells Neo, “You’re here because you know something. What you know you can’t explain, but you feel it.” This line hints at the movie’s theme of questioning reality and choosing your own truth.

Pro Tip:

If you have to announce your theme outright, it’s probably not working.

The best “theme stated” moments feel like ordinary lines until the rest of the story gives them weight.

Beat #3: Setup (1% – 10%)

The Set-Up beat introduces us to your protagonist’s ordinary world: who they are, what they want, and what’s missing from their life. It’s also where you quietly plant the seeds that will pay off later: supporting characters, early conflicts, and hints of the protagonist’s flaws.

Done well, this section answers two big reader questions:

- Why should I care about this character?

- What’s at stake if they don’t change?

Examples:

- In The Hunger Games by Suzanne Collins, we see Katniss caring for her sister, defying the Capitol, and hunting to survive. Every choice shows us her strengths, her flaws, and what she stands to lose.

- In Finding Nemo, Marlin’s overprotectiveness is established immediately. His tragic backstory and tight grip on Nemo set up the central conflict and emotional arc.

- In The Girl on the Train by Paula Hawkins, Rachel’s unreliable narration and unraveling personal life introduce us to her world while planting questions that drive the suspense.

Pro Tip:

The best set-ups feel effortless. You’re laying the groundwork for the entire story, but it should never read like an info dump. Show your character’s world through actions, choices, and small conflicts rather than long explanations.

Beat #4: Catalyst (10%)

The Catalyst is your story’s spark. It's he event that knocks your protagonist out of their comfort zone and sets everything in motion.

It usually happens around the 10% mark, and after this moment, life will never be the same.

This is also known as the inciting incident. Sometimes it’s loud and dramatic (a death, a betrayal, a shocking invitation). Other times it’s subtle but just as disruptive: a chance meeting, a secret revealed, a truth uncovered.

Examples:

- In The Da Vinci Code by Dan Brown, Robert Langdon is summoned to the Louvre after a murder. It's an invitation into a mystery that will consume the rest of the book.

- In Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen, Elizabeth’s world shifts the moment she meets Mr. Darcy. That awkward introduction sets up the conflicts, choices, and transformations ahead.

- In The Lion King, Simba’s life changes forever when Mufasa dies. It launches him on his journey of exile, identity, and redemption.

Pro Tip:

The best set-ups feel effortless. You’re laying the groundwork for the entire story, but it should never read like an info dump. Show your character’s world through actions, choices, and small conflicts rather than long explanations.

Beat #5: Debate (10% – 20%)

After the Catalyst upends everything, your protagonist hesitates. Do they act… or retreat?

This is the Debate beat: a moment of doubt, fear, and resistance before stepping into the unknown.

This section often explores:

- What’s at risk if they take action.

- What they’ll lose if they don’t.

- The internal and external forces pulling them in both directions.

Sometimes a mentor, friend, or side character offers advice here (often ignored until later). It’s less about solving the problem and more about showing how hard the choice feels.

Examples:

- In Jane Eyre by Charlotte Brontë, Jane wrestles with whether to stay at Thornfield after discovering Mr. Rochester’s secret. Her values and desires collide.

- In The Matrix, Neo literally faces the red pill vs. blue pill choice, embodying the tension between safety and transformation.

- In Moana, our heroine doubts her ability to sail beyond the reef and faces pressure from her family to stay, showing the pull between obligation and destiny.

Pro Tip:

The Debate beat works best when readers already know what the protagonist should do. But watching them fight it makes the eventual leap more satisfying.

Beat #6: Break Into 2 (20%)

This is the moment your protagonist chooses change. They leave their familiar world behind and step into an unfamiliar one, ready or not.

It marks the start of Act II: the “new world” where rules are different, stakes are higher, and nothing will ever be the same.

Sometimes the choice is deliberate. Other times, the character is dragged forward by circumstances. But either way, this is where the story truly begins.

Examples:

- In The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe by C.S. Lewis, Lucy and her siblings pass through the wardrobe and enter Narnia (a literal leap into a magical new world).

- In The Devil Wears Prada, Andy accepts the assistant job at Runway, stepping into a world of high fashion and brutal expectations she barely understands.

- In The Hunger Games by Suzanne Collins, Katniss volunteers as tribute, crossing the threshold from ordinary life into a deadly arena where survival depends on strategy.

Pro Tip:

The “Break Into Two” beat should feel irreversible. After this moment, there’s no going back, and readers should feel that shift as strongly as the protagonist does.

Beat #7: B Story (22%)

The B Story is where the secondary plotline kicks in… the one that adds depth, heart, and meaning to the main narrative.

It often introduces a new relationship that helps the protagonist face their flaws and ultimately learn the story’s theme.

This isn’t always a love story (though it often is). It could be a friendship, a mentorship, a rivalry, or even a philosophical conflict. Whatever form it takes, the B Story acts as a mirror that shows the protagonist who they are and who they could become.

Examples:

- In Good Will Hunting, Will’s therapy sessions with Sean act as the B Story, revealing Will’s fears and helping him confront his past.

- In A Man Called Ove by Fredrik Backman, Ove’s unlikely friendship with his new neighbors slowly breaks through his grief and stubbornness, reshaping his worldview.

- In Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse, Miles’s bond with the other Spider-heroes teaches him what it really means to wear the mask, deepening both the theme and his personal arc.

Pro Tip:

The B Story is where your theme breathes. If your protagonist learns a life lesson, chances are it’s this secondary plot (and the relationships within it) that make that lesson possible.

Beat #8: Fun and Games (20% – 50%)

This is where your story leans into its promise (the thing people came for). Often called the “promise of the premise”, these scenes deliver on what your book jacket or movie trailer teased.

Here, the protagonist explores their new world introduced in Act II. They might succeed, stumble, or both, but every moment shows us what makes this world unique.

It’s playful, tense, dramatic, or funny depending on your genre, and it’s where the stakes begin to simmer beneath the surface.

Examples:

- In Charlie and the Chocolate Factory by Roald Dahl, the Fun and Games beat is literally the tour. Readers delight in each magical, absurd invention before the factory’s darker truths emerge.

- In Jurassic Park, awe dominates early Act II: herds of brachiosaurs, baby raptors hatching, and wonder around every corner (until nature breaks loose).

- In Zootopia, Judy Hopps throws herself into policing the city, bouncing from one bizarre, comedic encounter to the next as she learns the rules of this new world.

Pro Tip:

“Fun and Games” doesn’t mean happy-go-lucky. It means delivering on your hook. Whatever you promised readers, this is where they get it.

Beat #9: Midpoint (50%)

The Midpoint flips the story on its head. It’s the turning point where the stakes rise, the tension tightens, and the protagonist’s journey takes on new urgency.

There are usually two flavors of Midpoint:

- False Victory – The protagonist seems to achieve what they wanted… but it’s an illusion. The “win” hides deeper problems or creates new ones.

- False Defeat – The protagonist suffers a crushing setback, hitting what feels like rock bottom, but this moment sparks growth and drives the story forward.

Either way, the Midpoint changes the rules of the game and forces the hero to reassess everything.

Examples:

- False Victory: In The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald, Gatsby finally reunites with Daisy. On the surface, he has what he wanted, but the cracks in their relationship and her loyalty begin to show.

- False Defeat: In The Fellowship of the Ring by J.R.R. Tolkien, the Fellowship loses Gandalf in Moria. It’s a devastating blow that deepens their fear but ultimately unites them.

- Stakes-Shift Twist: In Titanic, the Midpoint comes when the ship hits the iceberg. What began as a love story suddenly becomes a fight for survival.

Pro Tip:

A strong Midpoint raises the stakes and redefines the goal. After this beat, the story accelerates. There’s no coasting through Act II anymore.

Beat #10: Bad Guys Close In (50% – 75%)

The walls are tightening. In this beat, everything (external forces, internal fears, hidden flaws) starts pressing down on the protagonist.

Sometimes the “bad guys” are literal villains. Sometimes they’re the hero’s own doubts, insecurities, or destructive choices.

Either way, the tension escalates and the road ahead narrows. Every victory feels temporary, and every setback cuts deeper.

Examples:

- In The Hunger Games by Suzanne Collins, the Gamemakers turn up the pressure: fireballs, engineered alliances, and tracker jackers all push Katniss closer to breaking.

- In The Empire Strikes Back, the rebels are relentlessly hunted, Han is betrayed, and Luke walks into a confrontation he’s not ready for.

- In Toy Story 3, Woody and the gang are trapped at Sunnyside Daycare, surrounded by Lotso’s crew, and each failed escape makes their situation more desperate.

Pro Tip:

Don’t just make life harder. Force choices. The best “bad guys close in” beats push your protagonist to confront both external obstacles and internal flaws at the same time.

Beat #11: All Is Lost (75%)

This is the gut punch. The All Is Lost beat is where the protagonist hits rock bottom, when something “dies,” literally or figuratively, and the goal feels completely out of reach.

That “death” can take many forms:

- A literal loss, like a character’s death.

- The collapse of a plan, dream, or belief.

- The symbolic death of the hero’s old self, forcing them to face who they must become.

Whatever shape it takes, this moment should feel devastating and irreversible.

It’s the point where readers wonder, “How on earth are they going to recover from this?”

Examples:

- In Atonement by Ian McEwan, Briony realizes the damage her lie has caused and that some wounds can’t be undone.

- In Avengers: Infinity War, Thanos snaps his fingers and half the universe (including beloved heroes) turns to dust.

- In The Fault in Our Stars by John Green, Augustus reveals his cancer has returned, shattering Hazel’s hope for their future.

Pro Tip:

Make the loss personal. It doesn’t have to be big or loud, but it should dismantle something central to the protagonist’s identity, forcing them to confront what truly matters.

Beat #12: Dark Night of the Soul (75% – 80%)

After the All Is Lost moment, the protagonist faces the fallout… sitting in their grief, failure, or fear before they find the strength to rise.

This is the Dark Night of the Soul, the story’s most introspective beat.

Here, the hero confronts who they were, what they’ve lost, and who they must become to move forward. It’s often the moment where the theme clicks, when the truth hinted at earlier finally sinks in.

Examples:

- In Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen, Elizabeth processes Darcy’s letter and realizes how her pride and prejudice blinded her. It’s a quiet, internal transformation that reshapes the rest of the story.

- In Rocky, Rocky lies awake the night before the fight, accepting that he might not win, but deciding he can still prove his worth by lasting all fifteen rounds.

- In Inside Out, Joy breaks down after Bing Bong’s sacrifice, realizing that sadness has just as much value as happiness (a complete reframing of her worldview).

Pro Tip:

Give the reader space to breathe here. The Dark Night of the Soul works best when you let the weight of the previous loss linger before momentum shifts again.

Beat #13: The Break Into Three (80%)

After the darkness comes clarity.

The Break Into Three beat is where the protagonist experiences an epiphany, a shift in perspective that finally shows them the way forward. Armed with new understanding, they commit to action, stepping into Act III with renewed purpose.

This is where lessons from the B Story often click into place. Relationships, failures, and hard-won truths combine to give the hero exactly what they need to face the climax.

But not every Break Into Three signals victory. In tragic stories, the realization can come too late, adding emotional weight to the ending.

Examples:

- In Les Misérables by Victor Hugo, Jean Valjean decides to reveal his true identity to save another man from wrongful punishment, a decision rooted in his transformation.

- In The Dark Knight, Batman realizes he must become the villain Gotham “needs,” taking the fall for Harvey Dent’s crimes to preserve hope.

- In Mulan, after being cast out, Mulan spots the surviving Huns heading for the Imperial Palace and finds the resolve to save the Emperor.

Pro Tip:

The Break Into Three should feel earned. It’s the payoff for every failure, lesson, and relationship that came before, a moment of clarity that naturally propels the story into its climax.

Beat #14: The Finale (80% – 99%)

This is where everything comes to a head. The Finale is the story’s climax — the ultimate test where the protagonist applies everything they’ve learned to confront the central conflict once and for all.

The tone of this beat depends on the story you’re telling:

- In uplifting stories, the hero triumphs, bad guys fall, and the world is set right.

- In bittersweet endings, the goal might be achieved, but at great personal cost.

- In tragedies, the hero fails, sometimes because of fate, sometimes because of flaws they couldn’t overcome.

Examples:

- Triumphant: In The Return of the King by J.R.R. Tolkien, Frodo and Sam reach Mount Doom and destroy the Ring, ending Sauron’s reign.

- Bittersweet: In La La Land, Mia and Sebastian achieve their dreams but drift apart, sacrificing their love for their ambitions.

- Tragic: In Romeo and Juliet by William Shakespeare, miscommunication leads to both lovers’ deaths.

Pro Tip:

A great Finale ties back to the theme. The protagonist’s victory, loss, or sacrifice should feel inevitable… the natural result of everything they’ve learned, or failed to learn, along the way.

Beat #15: Final Image (99% – 100%)

The Final Image mirrors the Opening Image: a “before and after” snapshot that shows how the protagonist has changed. It’s the last emotional note of the story, the thematic resolution in a single scene or line.

If the Opening Image showed what was missing, the Final Image shows what’s been gained (or, in tragic stories, what’s been lost).

Examples:

- In The Hunger Games by Suzanne Collins, Katniss returns home after surviving the arena. The world hasn’t changed, but she has. Her defiance, relationships, and view of the Capitol are forever altered.

- In The Shawshank Redemption, Red walks barefoot along the beach, finally reunited with Andy… a quiet echo of his early despair and a visual symbol of hope fulfilled.

Pro Tip:

A strong Final Image lingers in the reader’s mind, offering closure without overexplaining.

Common Mistakes Writers Make with Save the Cat

The Save the Cat Beat Sheet is powerful, but like any tool, it’s easy to misuse.

Here are some of the most common mistakes writers make (and how to avoid them):

1. Treating the Beats Like a Formula

The beats are guidelines, not a checklist. Your story doesn’t need to hit every moment at the exact percentage mark.

Forcing scenes to “fit” the framework can make your writing feel mechanical instead of organic.

2. Confusing “Fun and Games” with Filler

This section isn’t just random antics in your new world. It’s where you deliver on the promise of your premise, the unique hook that drew your audience in.

Every scene here should either reveal character, deepen stakes, or move the story forward.

3. Forgetting the B Story

Many writers downplay or skip the B Story, but it’s often where the theme comes alive.

Whether it’s a romance, a friendship, or a mentorship, this subplot gives emotional weight to the climax and ties the protagonist’s growth to real relationships.

4. Over-Explaining the Theme

The Theme Stated beat should feel subtle (a quiet hint, not a lecture).

Let your characters and choices reveal the lesson instead of announcing it outright. If readers can predict your ending on page five, you’ve tipped your hand too soon.

5. Misunderstanding the Midpoint

The Midpoint isn’t just “something big happens.” It should raise the stakes and change the game, either through a false victory, a false defeat, or a massive twist.

Done right, this beat energizes Act II and sets up the second half of the story.

6. Forgetting That “Death” Can Be Symbolic

In All Is Lost, something “dies”, but that doesn’t always mean a literal death. It could be the collapse of a plan, a broken belief, or the loss of innocence.

Limiting yourself to literal deaths makes your story feel smaller than it is.

7. Copying, Instead of Customizing

Your favorite movies and novels might follow Save the Cat, but your story still needs its own shape. If your beats feel predictable, shake them up.

Invert expectations, bend pacing, or combine beats when it serves your story better.

Pro Tip:

Use Save the Cat as a map, not a cage. The best stories honor the structure without letting it overshadow character, emotion, and voice.

Save the Cat vs. Other Story Structures

The Save the Cat Beat Sheet is one of the most popular story frameworks, but it’s not the only one.

Writers have been using different structures for decades to shape compelling narratives. Each framework has its strengths, and knowing how they compare helps you choose the right one for your story.

Let's look at a few of the most popular ones…

1. Save the Cat vs. The Hero’s Journey

The Hero’s Journey, popularized by Joseph Campbell, is all about the internal transformation of the protagonist.

It focuses on archetypes and stages: the Call to Adventure, Meeting the Mentor, Crossing the Threshold, and so on.

By contrast, Save the Cat is more beat-driven and audience-focused. It leans heavily on pacing and emotional investment rather than universal archetypes.

- Best for: Writers who want a modern, character-driven roadmap with built-in story tension.

- Example difference: In Star Wars: A New Hope, Luke’s journey fits both structures, but Save the Cat emphasizes specific turning points like the Catalyst (meeting Obi-Wan) and Fun and Games (learning the Force), while the Hero’s Journey frames them as archetypal rites of passage.

2. Save the Cat vs. Three-Act Structure

The Three-Act Structure is the simplest and oldest model: setup, confrontation, resolution.

It’s broad and flexible, which makes it easy to use but light on detail.

Save the Cat essentially nests within the Three-Act framework, but it breaks those acts into 15 precise beats, giving you clearer milestones to hit without losing flexibility.

- Best for: Writers who like the familiarity of three acts but want more guidance on scene placement and pacing.

- Example difference: In The Devil Wears Prada, the Three-Act Structure says “Act Two is the confrontation,” while Save the Cat maps it more precisely: the Break Into Two (Andy takes the job), the Fun and Games (Andy explores the high-fashion world), and the Midpoint (Andy begins to lose herself to it).

3. Save the Cat vs. The Snowflake Method

The Snowflake Method, created by Randy Ingermanson, isn’t a beat sheet at all. It’s a planning process.

You start with a one-sentence summary of your story, expand it into a paragraph, then into character profiles, and finally into detailed scene-by-scene breakdowns.

Save the Cat, on the other hand, focuses on story flow and emotional pacing, not on the drafting process.

They actually pair well: Snowflake helps you plan scenes, while Save the Cat ensures those scenes land in the right places for maximum impact.

- Best for: Writers who want to pre-plot their novels and combine process with structure.

- Example difference: Using Save the Cat alone, you’d know you need a Midpoint twist. With Snowflake, you’d already have the specific scene outlined to deliver it.

Which One Should You Use?

It depends on how you think and what you need:

- If you want precise story beats and reader-focused pacing → Save the Cat.

- If you want mythic resonance and archetypal transformation → Hero’s Journey.

- If you want broad flexibility with fewer “rules” → Three-Act Structure.

- If you want help planning scenes and characters alongside structure → Snowflake Method.

Further Reading:

Save the Cat, The Hero's Journey, the Three-Act Structure, and The Snowflake Method are only a few of the many different types of story structures we can use. To learn about more, check out Kindlepreneur's comprehensive guide: Story Structure: 11 Plot Types to Build Your Novel

Since Save the Cat started as a screenwriting framework, you might wonder how well it translates to novels.

The answer: perfectly… as long as you adjust how you execute the beats.

Save the Cat for Novels vs. Screenplays

The Save the Cat Beat Sheet was born in Hollywood, but today it’s just as popular with novelists. The 15 beats stay the same, but how you execute them can look very different depending on your medium.

In a screenplay, you’re working within strict time and page limits: a standard film script is usually around 110 pages. Every beat lands almost exactly where the percentages suggest because pacing is critical.

Novels, on the other hand, give you more flexibility and depth. You have space to linger in character moments, explore subplots, and weave in multiple POVs. But that freedom also makes structure more important, not less. Without clear beats, it’s easy for Act Two to sag or your climax to arrive too late.

Here’s a quick comparison:

| Aspect | Screenplays | Novels |

|---|---|---|

| Length | ~110 pages (~110 minutes) | 70k–120k words on average |

| Beat Precision | Beats often land exactly at target percentages. | Beats can “breathe,” but ignoring them risks pacing problems. |

| Depth | Dialogue and visuals do most of the heavy lifting. | Room for interiority, subplots, and layered POVs. |

| Audience Expectation | Viewers expect tight, relentless pacing. | Readers enjoy slower burns and deeper immersion, but still need momentum. |

Bottom line:

The beats don’t change, but your execution does.

In screenplays, precision is survival. In novels, flexibility works, as long as you maintain tension and keep readers emotionally hooked.

Should You Use the Save the Cat Beat Sheet?

The Save the Cat Beat Sheet is one of the most flexible and widely used story structures for a reason: it works. Whether you’re writing a book, a screenplay, or a short story, these 15 beats give you a roadmap for pacing, tension, and character transformation.

But it’s not a formula. It’s a tool. Some stories follow every beat precisely. Others bend or skip a few. What matters is whether it serves your story.

The best way to find out? Test it.

Try mapping your story against the beats. See where the structure sparks new ideas, reveals pacing gaps, or deepens your character arcs. And if another framework works better, use that instead.

At the end of the day, every structure is there to do one thing: help you write stories readers can’t put down.

Good luck!

—

An earlier version of this article was authored by Jason Hamilton. It has been rewritten and expanded for freshness and comprehensiveness.